War Stories of the 2nd Bomb Group

During World War II

(and also some Related Post-War Stories too)

|

|

War Stories of the 2nd Bomb Group During World War II (and also some Related Post-War Stories too) |

|

Index of Stories on this Webpage

"Air Battle Over The White Carpathian Mountains" - Loy Dickinson

"The Uninvited Guests" - Bill Tune

"The Saga of Sweet Pea" - various contributors

"The Story of Skippy" - Brian & Beverly Sullivan

"Pilgrimage to Amendola" - Linda Gartz

"Reflections on the 65th Anniversary of Mission # 263" - Todd Weiler

"2nd Bomb Group Memorial Plaque at March AFB" - Dick Radtke

.

"The Uninvited Guests"

As a result of Mission #263 by the 2nd Bomb Group

on August 29, 1944 to peivoser oil refinery in

Czechoslovakia (Complete story described in

"Mission #263" on book page)

1st Lt. William S. Tune, Lead pilot of the 20th Squadron

and 23 other officers of the United States Army Air Force

were uninvited guests of the

German Government at Stalag Luft 1 prison camp

At Barth, Germany until the end of the war in 1945.

(during this period Lt. Tune filled his time drawing pictures

of their surroundings and living quarters these picture are

shown below.

Click on the Thumbnail print to enlarge it to readable size

Then click back (in the upper left hand corner) to return it to

thumbnail size.

Stalag Luft

Four Pictures Drawn By Bill Tune (20th Squadron Lead Pilot on Mission 263) while a POW

at Barth, Germany. Loy Dickinson (Group Vice-President) was also on this plane but

was housed in another barracks in the same POW camp, however, neither of the men knew that

until after the War ended and they were sent home.

Bill Tune's drawing of the camp at roll Call.

Tune's Home at Amendola Airbase in Foggia, Italy

|

The Saga of "Sweet Pea" courtesy of 2nd Bomb Group Association History "Defenders of Liberty"

These picture courtesy of former S/Sgt James Reiman 2nd Bomb Group

Sweet Pea returned to Amendola Air Base in Foggia, Italy and immediately upon landing came to a stop and collapsed as you see it here. The Flying Fortress was indeed a special plane.

The 2nd Bomb Group B-17 # 38078 on Mission 279 to Debrecen, Hungary Marshalling Yards on Sept. 21 1944

The Flight Crew Story

This raid produced one of the great flying fortress survival stories of the war. 2nd Lt Guy M Miller and crew of "Sweet Pea" were approaching the target when an 88mm anti-aircraft shell slammed into the plane's mid-section exploded, and nearly tore the Fortress in two. Huge sections of the waist on both sides instantly disappeared, control cables were cut, electrical and communications systems went powerless and silent. Half of the bombs fell out of the bomb bay, the lower turret was jammed with the gunner inside, and the explosion blew deadly debris in all directions. The left waist gunner, Elmer H Buss was killed instantly. The right waist gunner, James F. Maguire had multiple wounds but was saved by his back pack parachute serving as a flak suit, saving his life. The tail gunner, S/Sgt James E Totty was mortally wounded and died on the airplane. The radio operator, S/Sgt Anthony Ferrara was peppered like buckshot with shrapnel fragments in the chest.

The stunned crew started its battle for survival. Lt Miller and his copilot, Lt Thomas M. Rybovich struggled for control of the airplane and begin assessing what they had left to do it with. Most of the control cables were cut and his major control was through use of the engines which miraculously, were undamaged.

Lt. Miller thought about ordering bail out but decided against that when he learned he had one dead, three wounded, and one stuck in the ball turret. The wounded were gathered in the radio room for first aid. The bombardier/gunner, S/Sgt Robert R Mullen came back from the nose section and helped Sgt Gerald McGuire, upper turret gunner, bring the mortally wounded S/Sgt Totty from the tail to the radio room. McGuire did finally succeed in freeing Cpl William F Steuck from the ball turret. Later it was learned that turret was resting on only three safety fingers which were all that kept the turret from falling out of the airplane with Steuck inside. There were still six bombs hung up in the racks and Mullen climbed into the bomb bay and released them one by one with a screw driver.

Against seemingly impossible odds, Lts Miller and Rybovich now faced the reality of trying to nurse their mangled airplane and its battered crew across several hundred miles of enemy territory and almost 600 miles back to base. Navigator, 2nd Lt. Theodore Davich plotted a course and the pilots very gingerly set what was left of "Sweet Pea" on the long trek homeward. (This account is set out in the book "Defenders of Liberty" but I thought it such an outstanding achievement for this crew I would repeat it here.)

A First Hand Account of the Landing from Someone on the Ground The story as told by Jack Botts, Radio Operator, 414th Sqdn, 97th BG, Amendola, Italy. I was with the 97th BG, and we also had bombed the Debreczen target that day. I was standing on top of our plane, swabbing out the top turret barrels, when somebody pointed off to the south. There was this plane, making wide swings about 5 miles away, obviously trying to line up with our runways. We couldn't see damage from that distance, but were curious because of the odd maneuvering and the distress flares being fired. The plane passed us about 100 yards away as it landed, and we all yelled in surprise at the big hole through its waist. Four of us jumped into a jeep and drove over to where it stopped. The tail wheel had collapsed about half way down the dirt runway (between a steel mat and an asphalt strip), causing the plane to ride to a stop on the ball turret. We arrived at the plane with several other jeeps just as the crew was getting out. Somebody yelled that the ball gunner was still in the ball, so a couple other guys and I opened the turret and pulled out the gunner, who was in bad shape emotionally. He had not been able to move the ball nor communicate with the rest of the crew. One photo shows the turret hatch laying on the ground where it fell when we opened it. Another account that I read reported that the ball gunner had been freed from the ball on the way back from the target. It's a small matter, but it still stands out in my mind after nearly 65 years. My wife and I revisited Amendola in 1990 and the Italian air base that is there now was laid out much as it was way back then. That was one of the finest flying feats I had ever witnessed, since there were no tail controls in that plane. We in the 97th always had a good relationship with those in the 2nd BG, and I wish all its surviving members well. Best wishes to you.

The 2nd Bomb Group sheet metal and engineering crew that put "Sweet Pea" back together.

Putting the final touches on the body work. Most of metal came from parts of other Fortresses that had been junked. Sweet Pea was returned to duty and the original pilot, Lt Guy M. Miller took her up on her final mission. After that she was put into ferry service between Amendola and Casablanca (pictures compliments of former S/Sgt James Reiman)

The Ground Crew Story The story as told by S/Sgt James Reiman in an email received July 7, 2003

"A tough old bird flew again! I was inducted into the service in Saginaw, Michigan March 1943. After basic training it was off to sheet metal school 555 and then shipped overseas to Casablanca, North Africa for more training. Several months later several of us from the 339th Air Service Squadron were sent to Amendola Air Field near Foggia, Italy. We were immediately attached to the 2nd Bomb Group. I was in sheet metal work repairing many B-17s. On this day, September 21, 1944 the mission left our field early morning and after the mission was complete the main body of crews returned to our base on schedule as usual. We could tell that certain planes did not make it back. It had to have been about 2 hours later when we heard this lone B-17 with what sounded like engine trouble coming into our base. We were working in our repair area near the third runway, a dirt runway which was built for emergency landings. As I looked up at the B-17, the fuselage physically appeared to be swinging from side to side. I couldn't help but think that the pilot and co-pilot were doing one heck of a job bringing her in. They held her tail up off the ground as long as they could and the tail had not snapped off yet. It came to a stop just a short distance from our work area. Little did I know of the condition of the crew until later. I walked over to look at the damage which was a lot of sheet metal work and said to myself, "God, you could drive a army jeep through the hole of the waist of that B-17". It was resting on the ball turret under the B-17 as it collapsed from lack of stability in the center area. I examined the damage and realized that the only thing holding the plane together was the four metal struts on top and bottom of the fuselage. They had to have been very weak from the trip and the explosion of the shell.

It was standard procedure that we work in pairs to complete our work as it would speed up completion time. After we salvaged the parts, my partner, Emmett Shearer, of then Oakland, California, and myself repaired the plane. Sweet Pea went back into service shortly after but only as a transport plane. She had seen the last of combat by now. I cannot remember how many days and hours we put into the repair, but the area of repair was a vital part of the aircraft and everything had to be done just right. I do remember that Boeing considered it the most damaged B-17 that ever came back after being hit while on a mission. Emmett said he saw a picture of it in Washington DC at the museum and also in the Boeing Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.

To this day, I vividly remember the sight of Sweet Pea coming into the runway and what pride Emmett and I shared in completing what was told to us as an impossible task. Today E. A. lives in Washington State and I still live in Michigan. We can still recall those days and our comradeship throughout the war."

E. A. Shearer (left) and James Reiman (right) at Amendola. Thanks to a lot men for your help in this story! And sspecially Brian Reiman. ( DFC, webmaster)

|

||||

The Story of Skippy

The following picture of Skippy and his story of service was sent to us by Brian and Beverly Sullivan

(Recent note from Burt Thorman which helps complete the story.)

Dave: After my first visit to the website, I realized that the story of Skippy was incomplete. When the Group came into the Field, Skippy would race down the hardstand for Spinning's plane. The day that Spinning did not return, the dog was disconsolate and finally returned to the tent area. The next day or so, the Groups had him charging down to the hardstand, only to be disappointed. After that, hearing the planes returning, he would start to get up and then stop and sag in sorrow. It was a very sad thing to watch, until someone going home took him back to Peg Spinning - Burt Thorman

Ken W. Spinning and Skippy

In a June 2005 interview with Al Nash (429th Tail Gunner in Little Butch #42-29594), he recalled as mission intensity increased, Skippy became gunshy because of the amount of noise and clutter from nearby .50 cal's and had to be grounded. He would always be available when his master would prepare for a mission. The ground crew would have Skippy view the takeoff and he was always available for the landing.

The following newspaper photo was sent to the 2nd Bomb Group on 5/11/16 from Nate Wilburn of Great Falls, MT who wrote, "Was reading your tribute to Capt. Kenneth Spinning and his dog Skippy on the 2nd Bomb Group website today. I wanted to send you this newspaper photo and caption concerning them. The photo shows their B-17 nose art, Skippy and the Captain. I lived in the town mentioned in the caption, "Cut Bank, Montana", when I was a kid. I am assuming the photo was originally posted in the Cut Bank Pioneer Press which is the local paper there. Very sad story about the Captain and Skippy.

The following newspaper article was sent to the 2nd Bomb Group from Frank van Lunteren, Dutch historian, Arnhem, the Netherlands

Pilgrimage to Amendola

By

Linda Gartz

Linda Gartz and husband, Bill Lasko at Amendola

Amendola Military Air Base, Italy - Home of the 32nd Stormo (Bomb Wing)

My husband and I arrived in Rome on Friday, October 30, 2009. The trip was originally planned to explore the historical sites in Sicily with another couple, starting on November 2nd. But as I studied the Italian map, I realized that across the peninsula from Naples (from where we’d take the ferry to Palermo, Sicily) lay Amendola, the airbase where my uncle, Lt. Frank Ebner Gartz, a member of the 2nd Bomb Group, had been stationed during World War II.

It was only in April of 2009, that I first learned about Amendola, even though I’m in possession of more than 230 letters written between my uncle and my parents, my grandmother and neighborhood friends. Because the airmen were not allowed to disclose their exact location, the letters only described his location as “Italy.” But the envelopes held a clue, noting “49th Sq., 2nd Bomb Group” in the return address. After many dead ends attempting to locate former crewmates of my uncle through Air Force internet sites, I prevailed upon my brother, Paul, an aerospace engineer for Boeing, to come up with some ideas. He put me in touch with the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and through its representative, I learned about the 2nd Bomb Group website.

Todd Weiler, the 2nd Bomb Group’s historian, helped me download the list of my uncle’s missions and the crewmen with whom he had served. Sixty-four years after the end of World War II, I learned what no one in our family had ever known: that my uncle had successfully flown twenty-five missions between January 20th and May 1st, 1945, out of Amendola, Italy, near Foggia.

I determined that before meeting our friends in Naples, we would leave a few days early and make Amendola our first destination out of Rome. I knew there wouldn’t really be much to see there – the airbase, a few runways—but an inner voice told me I should go. After reading all of my uncle’s letters, I had come to know him—his quick wit, his easy-going, fun personality, his rascally nature (able to break a few rules—and a few hearts—to have a good time), and his achingly sweet side, unafraid to express feelings of love and loneliness.

I had flown in a B-17 back in June when the Liberty Belle came to the Aurora Municipal Airport, near Chicago. I had crawled under the pilot and co-pilot’s seats to get to the front of the plane, where my uncle had sat at the navigator’s table, directly behind the bombardier. I had looked out through the Plexiglas nose, envisioning the “carpets of flak” that had engulfed the aircraft, peered down through the Norden Bomb site, and handled the machine guns that bristled on all sides of the B-17, thinking of each manned by a young crew member, defending their ship and their lives against enemy fire. I had attended the 2nd Bomb Group Reunion in San Antonio and met many crewmembers, some of whom had flown with my uncle, but none remembered him. To complete the sense of “being there”—of seeing the area where my uncle had been stationed and served, I needed to go to Amendola—and this trip would probably by my last chance to do so. I looked at it as a pilgrimage of sorts, an opportunity to pay homage to all the men who served here so gallantly and to the young man whose death broke my family’s collective heart.

*****

Lt. Frank Ebner Gartz (everyone in the family called him by his middle name (ABE-ner) derived from my grandmother’s family name) had spent two years training for his eventual deployment overseas. From January, 1943, to December, 1944, he had criss-crossed the country, training in Santa Ana, California; Boise, Idaho; Biloxi, Mississippi; and Miami, Florida. He had attended the College Training Detachment in Stephens Point, Wisconsin, and went to navigation school in Hondo, Texas. Like most of the young men who served in the Second World War, he had virtually never been out of the confines of his small community. Growing up on Chicago’s West Side, knowing little of the rest of the country or the world, he, along with millions of other young American boys just out of high school, were being prepared to embark on an outrageously bold mission. Very simply, these “boys,” as everyone called them, were being sent forth to save the world from tyranny.

Ebner graduated from Air Force Navigation School on September 18, 1944, and the next month finally got hands-on experience in a B-17 when transferred to Rapid City, South Dakota. The rumor going around was that they would ship overseas by Christmas—and that’s exactly what happened.

He didn’t know exactly where he was headed, but on Christmas Day, 1944, he took off for Africa, spending New Years Eve in Marrakesh. He wrote home about it:

We stopped off in Africa for a while and had the time of our lives. It was the start of a 2 week vacation in which all we did was eat, sleep, haul wood and coal for our fire and play cards, raise hell, get drunk, and have a hell of a good time….We had a lot of fun in the Medina of Marrakech. It was off limits, sooo we saw all of it.

A little rule breaking seemed in order before the reality of combat, but bad weather kept them in northern Africa for two weeks before they finally made their way to Amendola. Of course, he was not allowed to reveal where he was, so all of his letters simply note the date and “Italy.”

His first mission was on January 20th, 1945, to bomb the oil storage at Regensburg, Germany, but he wasn’t assigned missions fast enough for his liking. Requiring thirty-five missions under their belts before he could return home, my uncle was eager to get them over with, despite the dangers. At the end of February, he wrote his buddy, Ted Symon about his lack of missions in the graphic language he reserved for friends:

I haven’t been flying much these days. I guess I’m on someone’s shit list or I haven’t been brownnosing enough. I’m through with that kind of crap. If they want to fly me, I could be back in the states in 4 mos. But I guess it will take me 7 or 8.

He would only have to complete twenty-five missions in the course of the next three and a half months, before the war came to an end. He navigated to targets in Austria: Vienna, Bruck, Trens, Linz and Salzburg; Italy: Verona, Bolzano, Malborghetto, Bologna (3 times between April 15-18), Germany: Ruhland and Regensburg again; Prague, Czechoslovakia; Maribor, Yugoslavia; and Sopron, Hungary.

He developed a philosophical attitude about death, as he wrote in one letter to my father about his mission on March 16, 1945:

Today I flew my 10th mission, and it was the hottest thing I have seen so far. There was more and bigger flak. We bombed an oil refinery in North Eastern Vienna and those people don’t like us to drop our presents to them.

Lt. Booms, my bombardier, had a rough time. He said that they threw everything they had at us including their kitchen sinks. Booms has to sit up in that Plexiglas nose where he can see all that stuff exploding around him. It sort of gets on his nerves. I was trying to explain to him that when your time comes it doesn’t matter where you are…your number is up, and that’s all there is to it.”

He flew his last mission to bomb the marshalling yards at Salzburg, Austria, on May 1st . He had made it through the war unscathed. His time was not up. Yet. when May 8th, VE Day, arrived, the family was overjoyed. The youngest son had made it through the war safely. He’d be coming home! But then he was presented with an amazing opportunity. He wrote his parents on June 8th:

I’m trying to get an appointment here in Italy flying for the 15th Air Force Headquarters, which will be flying Generals, Congressmen, and Ambassadors to various places in Europe. There’s a lot of fellows trying to get in, but I may have a chance.

He landed the job, and it was a honey: great contacts, a chance to see the world on the government’s dime. How could a twenty-one year old say no? He wrote:

The army is finally paying off for the times I flew over Vienna on a carpet of Flak.

He was stationed in Caserta, Italy, navigating to deliver VIPs all over the Mediterranean and Europe. He flew to Athens, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Egypt, the French Riviera (…where the girls wear a handkerchief and call it a bathing suit.), Frankfurt—and seemed to have a girl in every port. By August he was preparing to come home, but was still hoping for a pass from the Russians to visit his mother’s father in his home town in Romania.

His letters slowed down in late September and everyone assumed he was too busy to write, until my grandmother received a letter on October 17, 1945, dated October 5th, that stopped her heart:

Dear Mrs. Gartz:

The Hospital Command regrets to inform you that your son, 1st Lt. Frank E. Gartz, 0-2071572, 4th Air Service Sqdn, 62nd Troop Carrier Group, who was admitted to this hospital October 5, is now considered to be seriously ill. Frank is in the early stages of Infantile Paralysis, [polio, infecting the spinal cord] and it is impossible at this time to say what the outcome will be.

The outcome became clear a few weeks later when all the family’s letters, sent out in a flurry that horrid day, to console Ebner, came back with a bold DECEASED stamped across the front, a sickening reminder of what they couldn’t have known: Ebner was dead on October 12th, five days before they even knew he was sick.

The airbase at Caserta is no longer in existence, but I was determined to see Amendola, where Uncle Ebner had thwarted death twenty-five times, only to be brought down by the deadly stealth of a virus. Trying to make sense of it, I could only turn to Ebner’s own philosophy that he had shared in a letter to my father:

and if the good Lord has some other way [for me] to die, I’m not going to get it on the battlefield.

Having come to know my uncle through his letters, after having flown in a B-17, after meeting the men who had served in 2nd Bomb Group, I wanted to see Amendola--the very location – where Uncle Ebner had breathed the air, stared at the distant mountains, watched the sun sparkle on the Adriatic, climbed into his aircraft and navigated his crew to and from all those missions that helped bring World War II to a close.

*****

Several months prior to leaving for Italy, Todd Weiler, The Second Bomb Group’s historian, had provided me with an Italian Air Force contact. I wrote to Master Sargeant Antonio DiSipio, who responded to my email inquiry: “We are always pleased to meet relatives of the men who contributed to a page of Italian history, and in particular, to the Amendola Airbase.”

Sargeant DiSipio asked me to send a scan of our passports, and gave me his cell phone number to call when we exited the autostrada, near Manfredonia. From there he said it would be about a ten minute drive to Amendola.

After picking up our rental car at the Rome airport, we drove on the E-8, directly east through the mountains of Abruzzi and toward Pessara, on Italy’s Adriatic coast, then south on E55 to Foggia. I snapped a few photos of the surrounding fields, wondering if anything would look familiar, after all this time, to the men who had been stationed at Amendola. One thing I know they would not have seen were the dozens of high tech wind turbines bristling up across the countryside, their enormous blades rotating slowly in the autumn air.

Exiting at Manfredonia about 2:30, we called ahead to alert Sgt. Disipio of our imminent arrival and followed the signs to Amendola. On the road to the airbase, we passed a grove of olive trees and within minutes were driving alongside a chain link fence topped with coils of razor wire, the air traffic control tower rising in the distance.

As we pulled up to the entrance, the massive, green-barred gate opened to let us in. Sgt. DiSipio and two other Italian Air Force members flagged us to a parking spot. We exited our car to say hello to Sgt DiSipio, dressed in full uniform. He extended his hand. “Buon Giorno. Welcome to Amendola.” He introduced us to his assistant and the base’s historian, Sgt. Michele Rosito, the latter two dressed more casually in navy blue v-neck sweaters.

“Buon Giorno. Mi piacere.” (“Hello. I’m please to meet you,”) I said. My husband didn’t speak Italian, so we deferred to English, which Sgt DiSipio spoke quite well.

“Would you like some coffee?” He asked.

“Sounds wonderful.” It was the perfect suggestion after more than four hours of stressful driving. We followed the Airmen in their car down tree-lined roads cutting through the airbase, passing green dormitories where Italian Air Force trainees lived. In a few minutes we arrived at the officers’ club, which had a full “bar,” as it’s known in Italian–for coffee. “This is our drug,” he quipped. “We come here at least four times a day.” We each placed an order with the barristo, the man serving the coffee. “Un café lungo,” I requested – espresso with twice as much water as what the Italians routinely drink, to tone down the powerful brew. Two sips, and it was gone.

I looked around. One wall of the officers’ club was covered with plaques. On the other side of the wall was an enormous, gleaming mess hall, certainly not in existence in 1944-45.

After drinking our coffee, the officers led us outside to a large square, named in honor of a pilot killed during training exercises: Piazzale Magg. Pilota Giuseppe Carronne. (see photo). Several aircraft were on display: the Vampire, a British fighter; G91 Yankee (Italian), and a T33 American Trainer.

Sgt. DiSipio said that the airmen at Amendola deploy to Afghanistan. The Predator (a UAV) is routinely flown out of Amendola. We saw the predator’s hangar, but weren’t allowed to photograph it. Stenciled on the hangar was an outline of the Predator with the following warning (in English): “You can hide, but we’ll find you.”

Historian Michele Rosito then brought us to a small theater and set up an English version of a documentary he had produced. Using historical footage and photos, the documentary recalled the bombing of Foggia for of its strategic importance, the use of Amendola by the 15th Air Force as a base for bombing Axis positions, the laying of the pierced steel planking runway for the B-17 Flying Fortresses, stills and footage of the B-17s flying and dropping bombs, and various stills that captured life at the base. It concluded with the evolution of Amendola’s function as an airbase post-World War II to the present. Sgt. Rosito gave me several copies of his documentary, which will be made available for the Second Bomb Group website, barring any technical difficulties.

It was getting late, so I requested to see more of the outside of the base before sunset. The area where the 2nd Bomb Group’s tents had been set up during WWII was off limits, but we were able to go to the place where the B-17s had taken off on their missions.

As we drove around the base, Sgt. Rosito pointed out to us a couple of chunks of crumpled metal. They were all that remained of the metal grids, (probably “pierced steel planking”) that had been laid out on Amendola’s muddy fields more than six decades ago to form foundations on which the heavy B-17s were stored in between missions and to create the runway for take-offs and landings. Only these few scraps of twisted, rusty metal remained.

We then drove to a vast field, where Sgt. Rosito showed us where the original runway had been laid. I tried to envision, on this placid field, the sight of dozens of B-17s, loaded with fuel and bombs, engines revving, taking off one after another, flying into formation. I asked the Sgt. Rosito to take a photo of me pointing to where the runway had been (which should also be available on the website).

Our last stop was the museum Sgt. Rosito had created in honor of the Italian Air Force and the American 2nd Bomb Group. He had arranged several rooms of memorabilia to remind visitors of the role this airbase had played in winning World War II. On either side of the path leading to the entrance, the nose and tail of a now rusty bomb were pressed into the ground, like two sentinels standing guard. Inside, the first room was devoted to the commanders of Amendola over the years, their photographs spread across an entire wall. Nearby Sgt. Rosito had mounted a photo of Italian Airman, Fiorello LaGuardia, the man who would become the future mayor of New York. He had trained at Amendola.

Sgt. Rosito had arranged displays of respiratory equipment (gas masks), uniforms, boards of instrument panels that had been used to train pilots, models of aircraft, including the B-17, aerial photos of bomb sites, a fragment of an aircraft window (called tettuccio), the motor from a Bristol Orpheus 803-K13, and an aerial photo of the 2nd Bomb Group in formation “flying over the new Amendola Airfield in the spring of 1944” (see photo). I ended my visit to the museum by signing its guest book as a family member of a Second Bomb Group Navigator, and thanking them for their hospitality and devotion to Amendola’s history.

As the sun set, we bade goodbye to our hosts. Their gracious reception and eagerness to share Amendola’s past were evidence of their respect and gratitude for the American Airmen who had served here and whose courage brought eventual peace to Italy and the world.

Reflections on the 2009 65th Anniversary of Mission #263

By Todd N. Weiler

A review of my 2nd visit to the Czech Republic to commemorate the Battle of the White Carpathian Mountains.

Peering out from my lofty window perched up at 32,000-feet and jetting eastward, I strained to look out towards the horizon northward. A slight chill tingled up my spine at the wonder below. Never before had I an unrestricted view of all of cloudless Europe as I flew to Wein (Vienna) Austria to rendezvous there with my American companions, Roy and Fern Wager. We were to meet our Czech host Vlastimil Hela who would drive us the rest of the way to the Czech Republic for the 2009 WWII commemoration of the deadliest air battle in their country’s history.

I was thinking about that historic battle when in a moment without warning, I transcended 65 years back into time. August 1944 below me was a hellish place. The fate of the free world was in doubt. It was the heart of Europe and it was locked in total war…a world war… the second such war in a single generation. It was hard to believe looking at the patchwork quilt of colorful farms and cities below that a life and death struggle played out daily below me for many years. I thought of myself on a B-17 from the 2nd Bomb Group on one of its 412 missions of the war and feeling each revolution from four of the three-bladed props singing along chopping at the frozen air to bring the deadly cargo to bear on Hitler’s army below. Next came the Alps with their snow capped peaks and valleys glistening in the summer sun. The screen in the seat in front of me showed the outside air temperature read 52 degrees below zero. I imaged what each breath tasted like being deliver through a hardened rubber hose as my oxygen mask chafed at my cheeks after wearing it for eight hours straight. I imagined scraping my frozen breathe from inside the mask to take breaths better. I was 7,000 feet above the jagged mountains when I imagined the B-17’s struggling to climb over them loaded with high-octane gas and munitions with the pointed peaks perhaps a few hundred feet below me instead of the thousands of feet buffer I enjoyed today. Worst yet, I imagined what it would be like returning from completing a raid in a shot up B-17 knowing we’d have to cross this “high” way to get home. A slight queasiness in my stomach confirmed I had entered fully into the moment of the past.

As we descended to land I could see cities, railyards and small villages crammed along every river meandering through the countryside. Next came the refineries and electrical generating facilities…all prime targets in 1944. I wondered how many of those clearings in the woods were the result of a crashed Fortress. Such are my thoughts every time I fly over Europe.

But this time it would be a different trip. Since this was my second time, I knew more about what to expect. My first trip in 2007 was a total sensory overload. The different languages, the different foods, the different ways of doing things maxed out my ability to process it all. Not to mention that I was putting my fate into the hands of complete strangers I had only met via e-mail a year ago. It was a surreal experience with serendipitous moments every day.

As Vlastimil drove us past the old abandoned border checkpoints thanks to the European Union, and others centuries older than that, I was reminded the world is an ever changing place. Such fluidity of events can undermine one’s understanding of their place in the world. Hence I find learning more about my Uncle Jim Weiler’s past is that as a family foundation is learned it empowers one to better face their current challenges with strength and conviction. It reminds me others of my family and many veterans endured under far worse conditions.

I arrived on Tuesday August 25th, 2009 a few days ahead of the other Americans so I could take time to visit some of the other crash sites of mission #263 which claimed 10 bombers. So many things happened on this visit I could write a book about it. Some day I plan too! I’ll try and cover some of my epiphanyic moments, rather than a chronological recollection that others will likely share.

One of the first things I remember right after I arrived was going out to diner at a neighborhood restaurant in Bojkovice. While walking a few blocks to the tavern the road paralleled a small stream that went through the heart of the village, like almost all Czech cities. Looking closer, I could see schools of small trout gathered at each step dam. You don’t see that here in the states. We sat outside enjoying our meal until late in the night with no bugs. The fish must have been gobbling them up. That was cool!

Wednesday the 26th of August was an early rise for a long 65 mile road trip to reach the crash site of Bill Garland’s B-17 and Seaman’s B-17 near Liptal, CZ. Each day was sunny and warm (mid 80’s) and the nights into the 60’s for great sleeping. My prayers for cooler weather in 2009 paid off except for the 29th, which I’ll explain later. The winding roads are numerous and the ride was more of a roller-coaster ride than a mini-van full of Czech WWII history buffs buzzing through the countryside. The wind through the window was whirling and I was touring. Truly, the ultimate whirlwind tour!

While arriving at Metylovice we noticed an elderly lady with grey hair looking out a weathered window as we stopped. Roman Susil our guide, historian, host and translator inquired if she remembered the day Bill Garland’s plane fell from the sky in August of ‘44. Indeed the lady, Kveda Neuwirtova, did remember and provided lengthy details. That’s what so incredible about going over there now! The living witnesses are here and you can talk to them. No dried ink in a dusty textbook sitting on an obscure bookshelf…instead living, breathing people that can answer your questions. We then visited Garland’s crash site and stopped to say “ahoj” (hello in Czech) to a neighbor near the entrance road. The neighbor, Zdenk Cvictek also witnessed the crash in 1944 and also met Bill Garland in 1994. We went over to his house and in a minute he produced dozens of photos from Garland and Leo Zupan’s visit.

They are two of the 2nd Bomb Group vets that survived the August 29th air battle. 9 B-17’s and 1 B-24 all lost in 15 minutes.

From there we went to Palkovice where Russel Payne was killed bailing out. A road to the monument is named after him. It is located high on a hill that only hikers or a stout 4x4 can get to. It is a magnificent sight to see the town a thousand feet below. It’s a fitting site for an aviator’s end.

Next that afternoon we visited the crash site of Dyane Seaman’s B-17 #44-6369. It’s deep into a logging forest. As we got out of the vehicle we could walk around the area where the plane went down. The plane exploded in mid-air and showered the area with parts. After just a few minutes of walking around we found pieces of wreckage. I found an 8-inch strip of aluminum trim, a 6-inch chunk of green stained multi-strand wire and more. It wasn’t hard to find. Brush the thin layer of pine needles away from any small impact hole and one could see the discoloration of the soil to know something was buried there. Scavengers with metal detectors left the uninteresting things in a pile on a rock as sort of a mini shrine to the plane. Very cool!

Next we headed back to Velehrad where we got to interview the 90-year old priest Jan Marecek. He was one of three Catholic priests who held the burial service for the 28 U.S. airmen buried in the mass grave in Slavicin. 23-years old at the time and his first day on the job as a priest, his mind was sharp as he recalled every gristly detail. He remembers the sights, the smells, the weather and the temperament of the German Gestapo. He recalled the story about how the priests were forbidden to wear their vestments, no holy water and no citizens in attendance. As a further insult the American’s were to be buried as animals outside the Catholic cemetery, which was surround with a high wall. He described in detail how the bodies at first were laid neatly in the grave, but when the smell overwhelmed the German grave crew they dumped them in and arranged them with long sticks. As fate would have it, the next day the head priest went to another town after the burial. Citizens began leaving flowers on the gravesite overnight and the Gestapo threatened repercussions if it continued. With no priest to complain to it continued for several nights. Finally a few days later upon the priests return he was brought before the Gestapo and threaten with harm. After a long discussion the priest pleaded that the men were no longer soldiers and just ordinary humans that deserved a Christian burial. Ultimately the priests were successful in defusing the situation. Ironically, 65 years later the wall is gone and the cemetery grew so large, the grave is now centrally located along a main road into the church. The German plans to dishonor the Americans backfired and the grave is now a central viewing point in the cemetery. What a marvelous first day.

On a one of free mornings, I asked my friend Vlastimil to take me to my uncle’s crash site and also to where they salvoed his bombs before crashing. I wanted to visit the site privately because I wanted to reunite Jim Weiler with his brother Joseph. I had always had on my “bucket list” the dream of visiting Jim’s crash site with my father Joseph. Joe was in the 3rd Armored Division tank corps with General George Patton and despite all my arm-twisting he would never consider coming back. So now that my parents are deceased the best I could do was to bring my parents to Jim. So for the first time in 65 years, on a bright blue-sky morning, Joe and Jim were reunited as I poured my parents ashes next to Jim’s grave. As Vlastimil took a picture of the moment he managed to catch a special sight. While I was in a moment of reflection at the crash site memorial, a lone jet streaked a long bright contrail high overhead. Another sign from Jim was as a heard of cows walking up to the B-17 monument as well. I’ll explain that significance a bit later. I could sense Jim’s presence all around me.

On another morning, we visited the salvoed bomb craters were in a forest about a mile away on another hill near Bojkovice. The 10-foot deep 30-foot round holes still show the scars of the 250-lb. bomb’s impact on the forest floor. Looking upward one can see the scorched bark and shattered limbs of the tall fir trees that witnessed the shock of the blast. To stand in the holes and look up was a mighty emotional feeling. I had seen pictures of others in them, but now it was my turn. It’s very eerie to have the scar of a war wrap all around you.

I learned so much more on this trip than in 2007. Now I understood the context of the battle, met some of the survivors and had Czech translators at every moment. One amazing night I visited with Nic Mevoli, Roman Susil and Jana Turcínková. Nic’s grandfather Joe Owsianik was the reason I visited in 2007. Joe shook hands with the German fighter pilot that shot him down. I’ll save that story for the book.

Roman and Yana helped to translate. Roman showed up with about five historians from nearby Slovakia. From 10:30 PM until 1:30 AM we compared stories about the war, planes and mission #263. You should have seen the conversation start in English, get translated into Czech and then Czech into Slovak and then all the way back to me in English. It was a hoot. On and on it went for hours with many beers in between. I had so many questions. I learned the Slovak’s had new witnesses to my uncle’s crash. There were previously puzzling Czech translations of events that made no sense. Now I had the opportunity to press for details.

The first translated account in question said that some of my uncle’s crew where killed by the pressure change in their lungs when the remaining crew bailed out. That would have been only at about 1,000 feet according to witnesses. It made no sense until we talked about the German’s pulling the bodies from the wreckage. My account was they all went down with the plane, which is the story according to the sole survivor, co-pilot Irving D. Thompson who is now deceased. The Slovaks said, more than Thompson jumped. In fact five, Thompson plus four others made it out. Unfortunately the plane crashed with 11 of the 250 lbs. bombs aboard. Further more, because the plane was pursued by fighters to such a low altitude, the crew had little time and altitude to escape. Now came the new interpretation that the men bailed out, but were too close to the exploding wreck that the blast crushed them, hence the “air out of their lungs” finally made sense. It also supported the other witness reports that some of the dead men were lined up with their parachutes deployed. I also had new reports that my uncle’s body was not destroyed in the blast, but rather removed from the cockpit. It also fixes the explanation why some of the bodies are in individual graves instead of one common grave if the plane exploded with all aboard. This is why I go back. The details are there if you are willing to look, ask and listen.

On Friday afternoon, I finally rendezvoused with the rest of the American’s in attendance. Nic Mevoli, Joe Oswainik’s grandson from New York and his two friends Zach Baylin and Kate Susman were there. Donna Conway, the newly elected co-historian of 2nd BG and her husband Frank where there. Mike Meyrick is the nephew of Russel Meyrick the bombardier KIA aboard of B-17G, 42-97159. Mike brought his daughter Kelly Charles Meyrick and her son Alex and daughter Casey. Roy and Fern Wagner came from Tennessee. Fern Wagner is a sister of Joseph Edward Sallings, a left waist gunner who bailed out August 29th from B-17G, #42-97159. Joe hid from the Germans until the end of the war at the Pesat family home in a small village Preckovice, 2 miles away from the crash site. Terry Fox and Karl Rochford where a pair of British history buffs and former Royal army parachutists that Roman Susil convinced them this would be a great event.

We all rode up to the Sanov monument for Thayne Thomas’s B-17 “Big Time” crash site. We laid wreathes at two memorials. This is the site where the ball turret with Robert Flahive’s remains was found. We then retreated to the Sanov museum to see all the plane parts and history from the Zitnik Family museum in the City of Sanov. Later the Sanov Mayor treated the group to a meal of brats and beer at the local pub. It was a wonderful time of sharing and getting to know one another. A curious shape began to appear on the walls of the pub. The hanging light fixtures formed the outline of a formation of planes. As I pointed it out, more people began to notice and wonder. Truly some interesting signs were appearing on this trip.

We enjoyed fantastic weather throughout the week. Except for the anniversary day of Saturday, August 29th. That day the skies let loose 65 years worth of tears in the form of rain. The fog and rain dampened the hills and roads, but when we needed it most, it let up enough for us to do more wreath laying at the mass grave in Slavicin, Preckovice, and Rudice. In Slavicin I laid a special wreath from Kent Adiar, who’s nephew John H. Adair was killed aboard “Queen” piloted by James Weiler and crashed in Krhov. It read, “From all your friends in Texas.”

In Preckovice a few hours later a huge cloud burst dumped a soaking rain on a patiently waiting but growing crowd. I thought they would all leave as few had umbrellas or rain gear on. But they stuck it out and a new monument was placed on the former Pesat family home where gunner Edward Sallings hid from the Germans for almost a year until the end of the war. The gentleman who paid for the plaque was Jirik Fleischer, whose father took many of the famous photos of the Germans posing at the wreckage of “Queen” in August of 1944. Sadly, Jirik passed away just a short time after attending the 2011 2nd Bomb Group reunion in Colorado Springs.

Next, it was off to the famous little village of Rudice. This small town virtually shuts down and everyone from it comes to the small church cemetery to pay their respects to two U.S. Airmen that died nearby on mission #263. The continuing rain cancelled the out-door mass that was planned at the site where Russel Meyrick died after his chute failed to open. Instead everyone went to the small chapel next to the cemetery where a commemorative mass was held. Later everyone went to the community building/fire house where all the dignitaries and people toasted each other and ate a hardy potluck meal. A little bit of slivovitz was consumed as well. OK, a lot was consumed.

Despite the rain, the Meyrick family wanted to see the actual site were Russell died. So we took a van about a mile out of town to the field were Russell died. As we arrived the forests were still full of wisps of white fog blowing into the dense fir trees and the fields held a light rain. As the family exited the van, the sun finally dramatically broke through the clouds to the west and shot golden beams of yellow light deep underneath the dark forest canopy. It illuminated the white floral wreath in a radiant light placed by the villagers in anticipation of the out-door mass. My knees weakened and my eyes watered as I realized what was happening.

I ran 100 yards out into the neighboring open meadow, turned around to look back and saw in the sky a sign of Russell's approval. A huge rainbow was spread end-to-end over "the place they call America"! Four generations of Meyrick's where getting reunited in a very, very special way. The locals so respect this place that they call it “America”. Imagine naming a part of your town after another country’s sacrifice. That’s what they do here. They never forget. What words can replace this incredible photo? The Czech patriotic spirit seems to know no limit for our veterans.

The next day the sun came out and the rain disappeared. It was the day to honor Jim Weiler’s airplane memorial. We started with a mass in Bojkovice and then headed to the Slovak-Czech border near the city of Vyskovec where Merrill Prentice’s plane (B-17G, #42-31885) crashed. We laid wreaths and paid our respects. Next it was back to Krhov and my uncle’s Jim’s crash site.

While at City Hall for a lunch before the event, one of the Czech historians came up to me and said, “ I found “Queen”. I noddingly said thank you as I too found pieces of her at the crash site earlier in the week. He said, “No, No I found a picture of Queen…on Internet!” To make a long story short, Radovan Flait, a local Czech historian found a picture of a B-17 with the tail numbers of 23204 and the last digit was missing. Jim’s plane was 232048. We had a date and a mission number from the photo. After two weeks of eliminating all the 23204 possibilities, indeed the final result is it was “Queen” in a full picture. And to think that it came to life 65 years to the date it was destroyed. That was a surreal twilight-zone moment for me. In just two years, I’ve gone from just a tail photo to a complete photo. Jim sure knows how to pull strings and put things in my lap.

As we arrived at the Krhov site, crowds had to walk up a steep hill. The all-day rain the day before didn’t help those walking in the muddy fields. Still they came. As the service began, a herd of curious cows came over to the memorial and looked attentively. I couldn’t help but think my Grandfather Jake was making his presence known. It was like a manger scene from Christmas Eve. Hollywood can’t make this stuff up. You see, it was Jim’s father Jake who was the veterinarian that took care of all the cows around Burlington, WI. A fitting or moooving tribute I’d say.

We again laid wreaths and various dignitaries paid their respects with speeches and salutes like the other ceremonies. At the close of the ceremony I brought out the Silver Bracelet and placed it on the grave for photos. I also posed with it and Joska Spelina, the Czech citizen who returned the bracelet to the family 43 years ago. The circle of life story was complete. You’ll have to read the “Story of the Silver” bracelet to fully understand.

Finally we finished the day with a relaxing backyard party at Vlastimil Hela’s home. It was our last chance to compare notes and thank everyone, hosts and guests for making this event so memorable. We had to be at the Wein airport at 3 AM so it was a short night. On the plane ride home all I could think about is how my next visit will go and looking forward to enjoying it.

The Czech people in this story are remarkable. Not only did they endure countless threats to their lives from on the ground and in the air, but also in the heat of the moment of deciding what choices to make, they rightly made the human choice to help. How many people today would cave into the current political correctness and put that above human worth. Thanks to their efforts, many American fliers survived. Thanks to their continued devotion to do the right thing, my uncle’s silver bracelet was returned. Thanks to their values the deeds of the dead Americans are not forgotten or discarded. They are revered, honored and permanent reminders are in place to remind future generations what the sacrifice for freedom is all about.

I can unequivocally say if you have any interest in visiting this area and want to see any of the sites, you would be welcomed with open arms. Obviously the August 29th is the pinnacle date if you want to see how the townspeople respond. You will be changed and you will realize that not all America patriots live in America. Some people still know how to do the right thing.

Here’s wishing a solemn and thankful anniversary to all those who we remember today, August 29, 2012, 68 years later. May your deeds be long remembered.

Friday, Aug 28, 2009

04.00 - 05.00 pm - Sanov (B-17G, 42-38096), laying the wreaths at the crash site

05.30 - 07.00 pm - museum in Sanov *

Saturday, Aug 29, 2009

11.00 - 12.00 am - museum in Slavicin, incl. the presentation of the DVD 'Gray Eagles'

12.00 - 01.30 pm - lunch

01.30 - 02.00 pm - laying the wreaths at the mass grave of 28 American fliers at Slavicin cemetery

03.00 - 03.30 pm - unveiling of the memorial plaque in Preckovice

04.00 pm - Rudice (B-17G, 42-97159), laying the wreaths at the Joe Marinello's and Russell Meyrick's grave, holy mess at Meyrick´s tree, discussion with the local people

Sunday, Aug 30, 2009

09.30 - 10.30 am - holy mass in Bojkovice

11.00 - 12.00 am - Vyskovec (B-17G, 42-31885), laying the wreaths at the crash site

12.30 - 01.30 pm - lunch in Bojkovice

02.00 - 03.30 pm - Krhov (B-17G, 42-32048), laying te wreaths at the crash site

04.00 - 06.30 pm - discussion with the local people in Bojkovice, Silver Bracelet Story

2nd Bomb Group Memorial Plaque Unveiled

15th Air Force Wall, March AFB, California

September 25, 2002

General James H. Doolittle First Commander of the 15th Air Force 1943 (Second Bomb Group Plaque covered in blue).

President Richard Radtke unveiling the new

2nd Bomb Group Plaque with former president

Edwin (ED) Hodges.

Four members were POW during World War II: Loy Dickinson, Earl W. Martin, Edgar McDonald, and Jack Kellog.

Historian for the 2nd Bomb Group

Earl W. Martin presents copies of

"Defenders of Liberty" and

"The Second Was First" To Hisperia High School Color Guard for the Event.

Chris Oren of the AF JROTC unit is accepting.

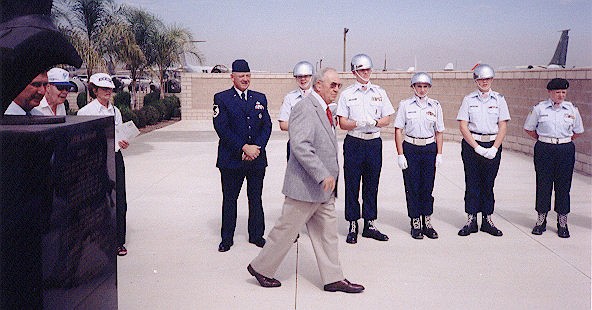

President Richard Radtke going past the Color Guard to Unveil the Plaque.

The Color Guard for the Unveiling of the Second Bomb Group Plaque at March AFB was furnished by the 872nd AF JROTC Squadron from Hisperia High School, California.

Plaque Sponsor: Second Bombardment Association.

Members of the 2nd Bombardment Association present at the Dedication Standing (Left to Right) Virgil Gergen, Earl W. Martin, Richard R. Radtke, Edwin S. Hodges, Jack Kellogg and Lewis Moore kneeling (Left to Right) Loy Dickinson, Jim Lang and Richard Wood.

Nadine Amos, to her right her daughter Susan and her son Barry, to her left

her son Bradley and his wife Ida, kneeling is their son Todd, all present at the Dedication.

Vic and Marg Metz were present at the dedication.

Back Home Forward: 15th Air Force